In October 1950, Alan Turing published “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” in the journal Mind, asking a deceptively simple question: “Can machines think?” Rather than engage in abstract metaphysics, Turing proposed a pragmatic experiment—the Imitation Game—that forever changed how we discuss machine intelligence.

Replacing Metaphysics with a Game

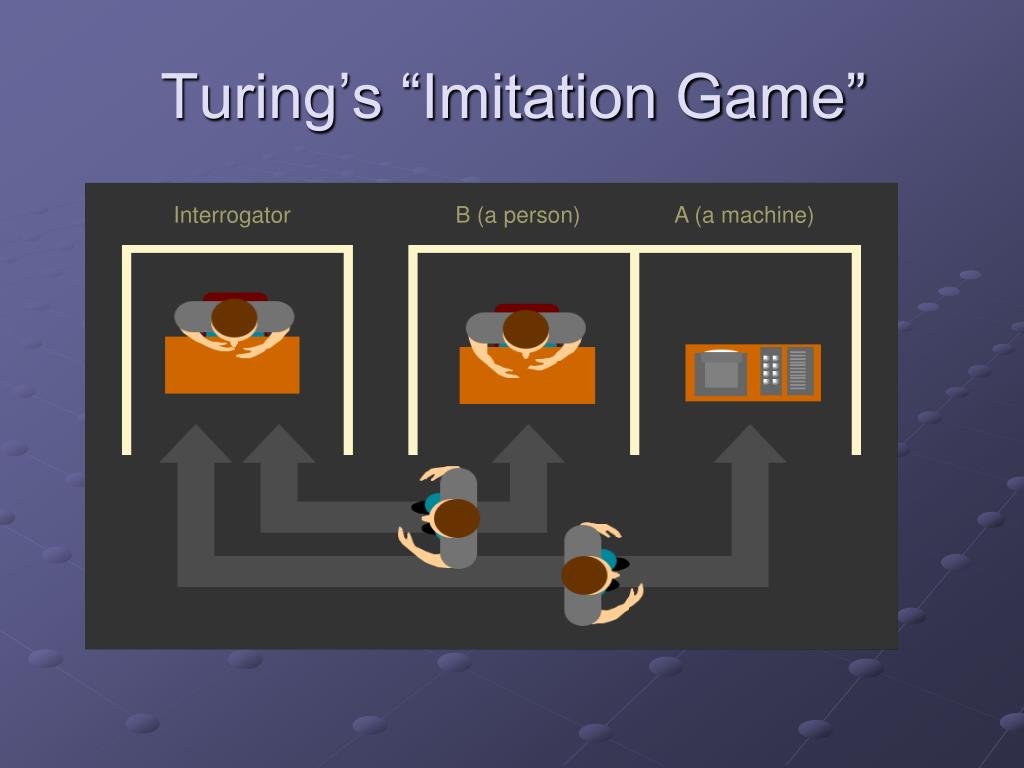

Turing’s first move was philosophical judo: he sidestepped the ill-defined word think and replaced it with behave indistinguishably from a human in conversation. In the Imitation Game, an interrogator in one room exchanges typed messages with two unseen entities—one human, one machine—and must decide which is which. If the machine can fool a skilled questioner a significant fraction of the time, Turing argued, we should grant it the attribute of intelligence.

This behaviorist criterion was radical. It grounded “intelligence” in observable performance rather than invisible mental states, foreshadowing later functionalist theories in cognitive science. It also democratized evaluation: laboratory equipment was unnecessary; only linguistic wit and teleprinter lines were required.

A 70-Year-Old Metric That Still Bites

Turing predicted that by the year 2000 machines would fool judges 30 % of the time in a five-minute test. Reality has lagged behind that optimism: systems from ELIZA to chatbots in the Loebner Prize competition often exploit conversational tricks but seldom maintain deep, sustained deception. Yet the metric endures because it sets a clear, falsifiable bar—far more concrete than “machine consciousness.”

Crucially, the test is domain-general: trivia, ethics, poetry—all fair game. This breadth distinguishes it from task-specific AI benchmarks and keeps the conversation centered on human-level versatility.

Objections and Counter-Objections

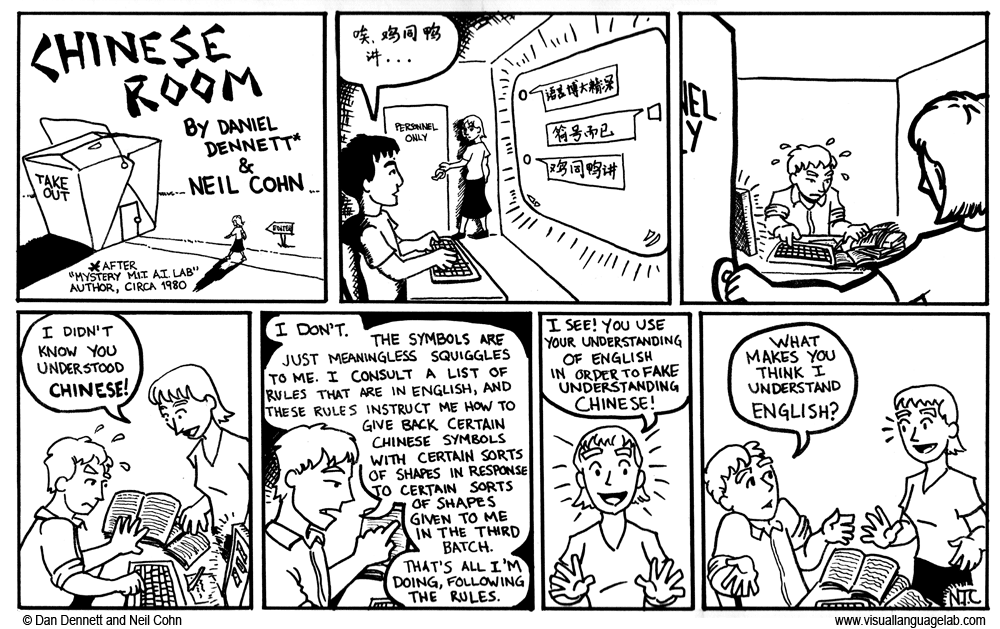

- The Chinese Room (John Searle, 1980)—a person following symbol-manipulation rules could simulate Chinese without understanding it, suggesting that passing the test need not entail semantics or consciousness.

- Total Turing Test (Stevan Harnad, 1991)—true intelligence would also require perceptual and motor capacities, not just text.

These objections do not refute Turing’s empirical claim; they expose the gap between functional equivalence and phenomenal experience. In doing so, they illustrate the continuing philosophical richness of Turing’s thought experiment.

Turing anticipated nine major criticisms, from the “mathematical objection” (Gödel-style undecidability) to the “Lady Lovelace objection” that machines can do only what we program them to do. He countered by pointing to learning machines that could re-write their own rules. Modern philosophers added fresh attacks:

From Teleprinters to Large Language Models

Today’s transformer-based systems generate prose that routinely astounds lay users; yet longer dialogues often reveal brittle reasoning or factual hallucinations. The Turing Test remains a useful stress test precisely because it is adversarial: judges probe edge cases, follow-up questions, and contextual nuance. Researchers now track “confusion times”—how many back-and-forths before the model slips—to quantify conversational robustness.

Beyond evaluation, Turing’s paper laid conceptual tracks for machine learning. He proposed training a “child machine” through rewards and punishments, an early sketch of reinforcement learning. This vision resonates in modern self-play systems like AlphaGo and in the large-scale pre-training of language models.

Why the Imitation Game Still Matters

- Operational Clarity – It offers a crisp, empirical yard-stick in a field often muddied by hype.

- Ethical Mirror – By forcing us to articulate why a machine’s behavior convinces us, it exposes our own anthropocentric biases.

- Research North Star – Even when we devise new benchmarks (from Winograd schemas to BIG-bench), the Turing Test lurks as the ultimate integration challenge: open-ended, creative, and human-facing.

Conclusion

Alan Turing fused engineering pragmatism with philosophical depth. The Imitation Game reframed the quest for artificial intelligence as a publicly testable claim rather than a metaphysical puzzle. As today’s AI systems edge closer to passing extended, unscripted conversations, Turing’s 1950 vision invites us to ask not only whether machines can think, but what kind of thinking we truly value.