When twenty researchers gathered on the leafy campus of Dartmouth College in the summer of 1956, they were not merely attending another academic workshop—they were inventing a new field of study. Over eight intense weeks, the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence coined the very term artificial intelligence and sketched an audacious research agenda that still guides the discipline nearly seventy years later.

A One-Page Proposal that Changed Everything

Months earlier, a concise, now-famous proposal—just over 600 words—had set the stage:

“Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.”

Penned by John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon, the document asked the Rockefeller Foundation to fund a “two-month, ten-man study” at Dartmouth College. Their request was approved, and the meeting was scheduled for 18 June – 17 August 1956.

Naming a New Science

McCarthy insisted on the neutral phrase “artificial intelligence,” distancing the work from cybernetics and automata theory. The name stuck, providing a conceptual umbrella broad enough to unite researchers interested in logic, learning, language, and neural networks under one brand-new banner.

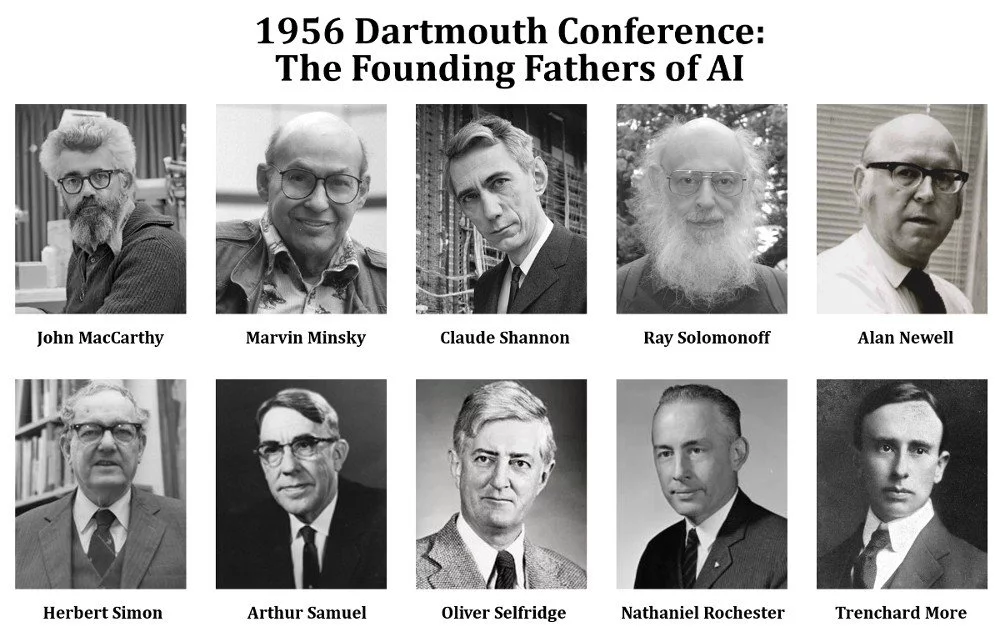

The Founding Four—and Their Guests

The organizers formed the conference’s intellectual nucleus:

- John McCarthy – a young mathematician defining AI’s vocabulary and future Lisp language.

- Marvin Minsky – Princeton-trained polymath exploring neural nets and symbolic reasoning.

- Claude Shannon – father of information theory, bringing probabilistic thinking.

- Nathaniel Rochester – IBM engineer eager to program the first intelligent machines.

They were joined at various points by luminaries such as Allen Newell, Herbert Simon, Oliver Selfridge, Ray Solomonoff, and Trenchard More. Although attendance fluctuated—some stayed days, others the whole summer—the core group met daily, debating how machines might form concepts, use language, and even improve themselves.

Ambitions as Large as Intelligence Itself

The agenda was breathtakingly broad. Besides the now-iconic conjecture, the proposal listed concrete targets:

- Create machines that use language and form abstractions

- Develop programs that solve problems reserved for humans

- Explore self-improvement—machines that rewrite their own code

Given computers of the 1950s filled entire rooms and stored only kilobytes, these goals were nothing short of visionary.

Funding the Dream

Securing resources was an achievement in its own right. McCarthy and Shannon lobbied the Rockefeller Foundation, arguing that a modest grant could unlock strategies for machine thinking. The Foundation, intrigued by the interdisciplinary promise, ultimately underwrote travel and stipends—an early example of philanthropic investment seeding disruptive technology.

Brainstorming, Chess, and Chalk Dust

Accounts describe a free-wheeling atmosphere: participants scribbled proofs on blackboards, played lightning chess in dorm rooms, and took turns presenting nascent ideas—Newell and Simon’s Logic Theorist, Selfridge’s Pandemonium model, Rochester’s early pattern-recognition schemes. Debate often spilled onto Dartmouth’s verdant lawns, underscoring how interdisciplinary cross-pollination—mathematics, psychology, electrical engineering—was essential from day one.

Immediate Ripples and Lasting Waves

While the workshop produced no grand unified theory, it forged personal networks and research trajectories that shaped the next decades. Newell and Simon launched symbolic AI at RAND; McCarthy wrote Lisp and founded MIT’s AI Lab with Minsky; Shannon’s information-theoretic lens influenced probabilistic reasoning. Crucially, the conference’s manifesto—machines can in principle simulate intelligence—became the field’s north star, spurring both triumphs (expert systems, deep learning) and periodic “AI winters” when progress stalled.

Conclusion: The Conference that Became a Compass

The Dartmouth Conference is often called the “Constitutional Convention of AI,” and the analogy fits. By naming the field, articulating its grand challenge, and marshaling a cadre of brilliant minds, it set a research direction whose influence is felt in every neural network and language model today. As we marvel at systems that translate speech in real time or generate code, we stand on the shoulders of a small summer gathering in Hanover, New Hampshire—a testament to how bold vision and collaborative curiosity can birth entirely new sciences.